The 7th of September has been a public holiday in Mozambique for the last 46 years. For most people it is another day off, a moment for relaxation and if pressed hard for an answer something vaguely associated with the liberation of the country. Mozambicans will have difficulty in recalling the events in 1974 because it was actually the beginning and end of a series of events that lead to a change that few had expected.

The 7th of September has been a public holiday in Mozambique for the last 46 years. For most people it is another day off, a moment for relaxation and if pressed hard for an answer something vaguely associated with the liberation of the country. Mozambicans will have difficulty in recalling the events in 1974 because it was actually the beginning and end of a series of events that lead to a change that few had expected.

In Joseph Hanlon’s book The Revolution Under Fire there is only one short chapter describing the events that led up to the 7th of September – the day on which Mario Soares the Portuguese Foreign Minister and Samora Machel agreed to the independence of Mozambique from Portugal. Private accounts released to newspapers however provide greater exposure to just how divided public opinion was on the matter and the reason why any other outcome was not viable.

Most of the events leading up to the 7th September Accord, the Acordos de Lusaka, actually had their beginnings in the Carnation Revolution of Portugal in April of 1974. Portugal had been fighting the guerilla movements in its colonies in Africa for more than 10 years and there was growing realization that the major wars in Angola and Mozambique were not sustainable. Angry conscripts and military officers, outnumbered and under resourced believed they could no longer fight the war. Alas, it was not just the futility of war but the larger significance of propping up a fascist regime that had long subverted the freedom of the Portuguese people that was hardest to swallow.

These men soon formed what was known as the MFA (Movimento das Forcas Armadas) that overthrew the Estado Novo regime and hastened the decolonization process. By forming agreements with independence movements such as FRELIMO in Mozambique, there was a tacit understanding between the new Portuguese authorities and the incumbent movements that there was no longer an interest to fight a war. In fact, both sides had much more to gain by putting their arms away.

These men soon formed what was known as the MFA (Movimento das Forcas Armadas) that overthrew the Estado Novo regime and hastened the decolonization process. By forming agreements with independence movements such as FRELIMO in Mozambique, there was a tacit understanding between the new Portuguese authorities and the incumbent movements that there was no longer an interest to fight a war. In fact, both sides had much more to gain by putting their arms away.

In Mozambique, however there were conflicting interests that both supported and rejected the idea of decolonization. Those who heavily supported Portuguese industrialization and capital bemoaned the growing threat that communism would bring; children of European settlers supported a democratic and nationalist perspective demanding autonomy from Portugal but with the right of Mozambicans to decide their own political outcome; Africans who had long been marginalized did not trust a leadership that was not African and for the vast majority of transient expatriates who neither had capital nor family interests in Mozambique it was about scrambling for safety; not getting caught in war that was essentially someone else’s problem.

In Mozambique, however there were conflicting interests that both supported and rejected the idea of decolonization. Those who heavily supported Portuguese industrialization and capital bemoaned the growing threat that communism would bring; children of European settlers supported a democratic and nationalist perspective demanding autonomy from Portugal but with the right of Mozambicans to decide their own political outcome; Africans who had long been marginalized did not trust a leadership that was not African and for the vast majority of transient expatriates who neither had capital nor family interests in Mozambique it was about scrambling for safety; not getting caught in war that was essentially someone else’s problem.

And so in the months between May and June 1974, there were several bombings, strikes, demonstrations and spontaneous public gatherings which disrupted any possibility of normalcy as the various groups jostled with each other to put forward their opinion on how to move the country forward.

The signing of the Lusaka Accord was the final straw for those could not accept a handover to FRELIMO. On the evening of 6th of September, a small group of African youth transporting themselves on a truck dragging a torn Portuguese flag in central Lourenco Marques were intercepted. The men were dealt with savagely and a FRELIMO flag they were waving was ripped and destroyed.

The signing of the Lusaka Accord was the final straw for those could not accept a handover to FRELIMO. On the evening of 6th of September, a small group of African youth transporting themselves on a truck dragging a torn Portuguese flag in central Lourenco Marques were intercepted. The men were dealt with savagely and a FRELIMO flag they were waving was ripped and destroyed.

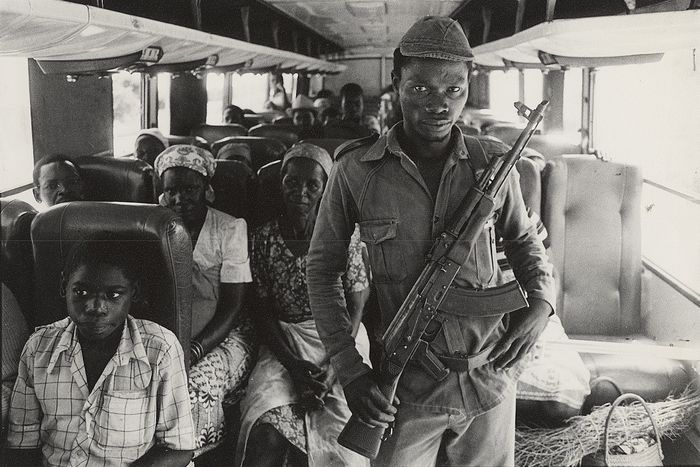

On the 7th of September, the headquarters of the national broadcasting service was occupied by an angry group of white settlers opposed to the FRELIMO regime’s undisputed takeover. They ceased the radio equipment and began broadcasting appeals to the settlers in other provinces to reject the accord. All these plans ran contrary to what had been decided and the troops from the Portuguese army were sent to deal with the “panicked whites”. FRELIMO soldiers were also sent to join the troops to ensure that order was restored.

In response to the disturbance, the Africans in suburbs surrounding Lourenco Marques were much less forgiving. In the next few days there were more reports of clashes; young African men stopping cars, setting them alight and attacking the passengers. There were reports of deaths and the central hospital recorded increases of patients. The road leading to the airport was also the site of many atrocities.

It should also be mentioned that all these events were not perpetrated exclusively along racial lines. There were Africans who did not want Mozambique to be autonomous and supported the many whites. There were also whites who supported FRELIMO.

In the days following the 7th of September, a transition government was drawn up and finally independence – the effective handover of Mozambique to its people was scheduled to take place on the 25th of September 1975.

Credits to images: DW, RTP