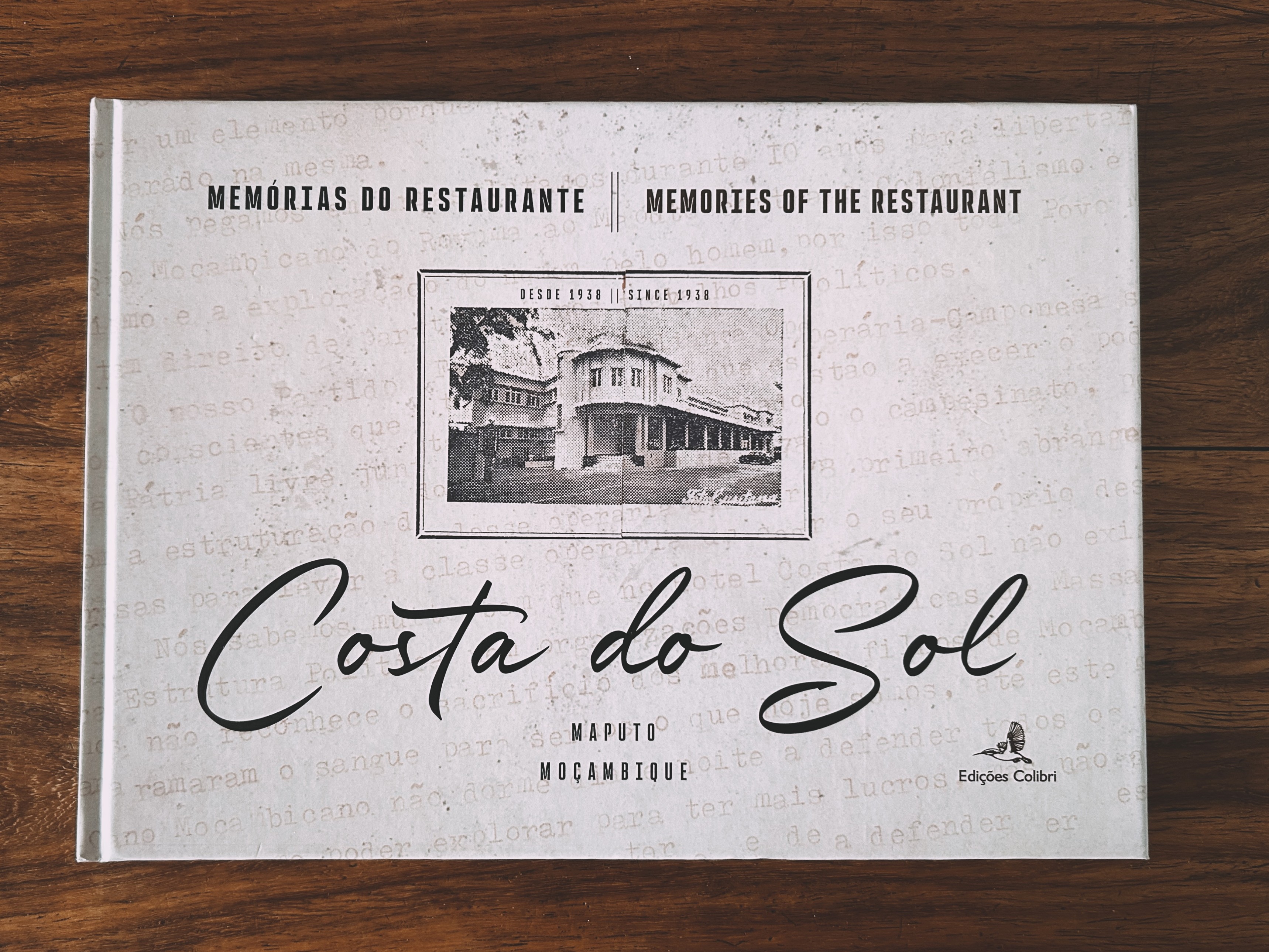

Costa do Sol, the book about the decades old restaurant is finally available in Mozambique after being reported in this blog. At a whopping 60 dollars a piece (in Maputo), it is not likely that too many folks will splurge on it. This writer, riddled with the fear of missing out, over a title that may easily go out of print and be forever lost to the dark confines of Mozambican history, did just that.

The book with a selection of photos from the Petrakakis’ personal archives and others widely seen on the internet folded together into somewhat of a light-hearted reflection on what became to be more than just a restaurant at the northern fringe of the then Lourenco Marques.

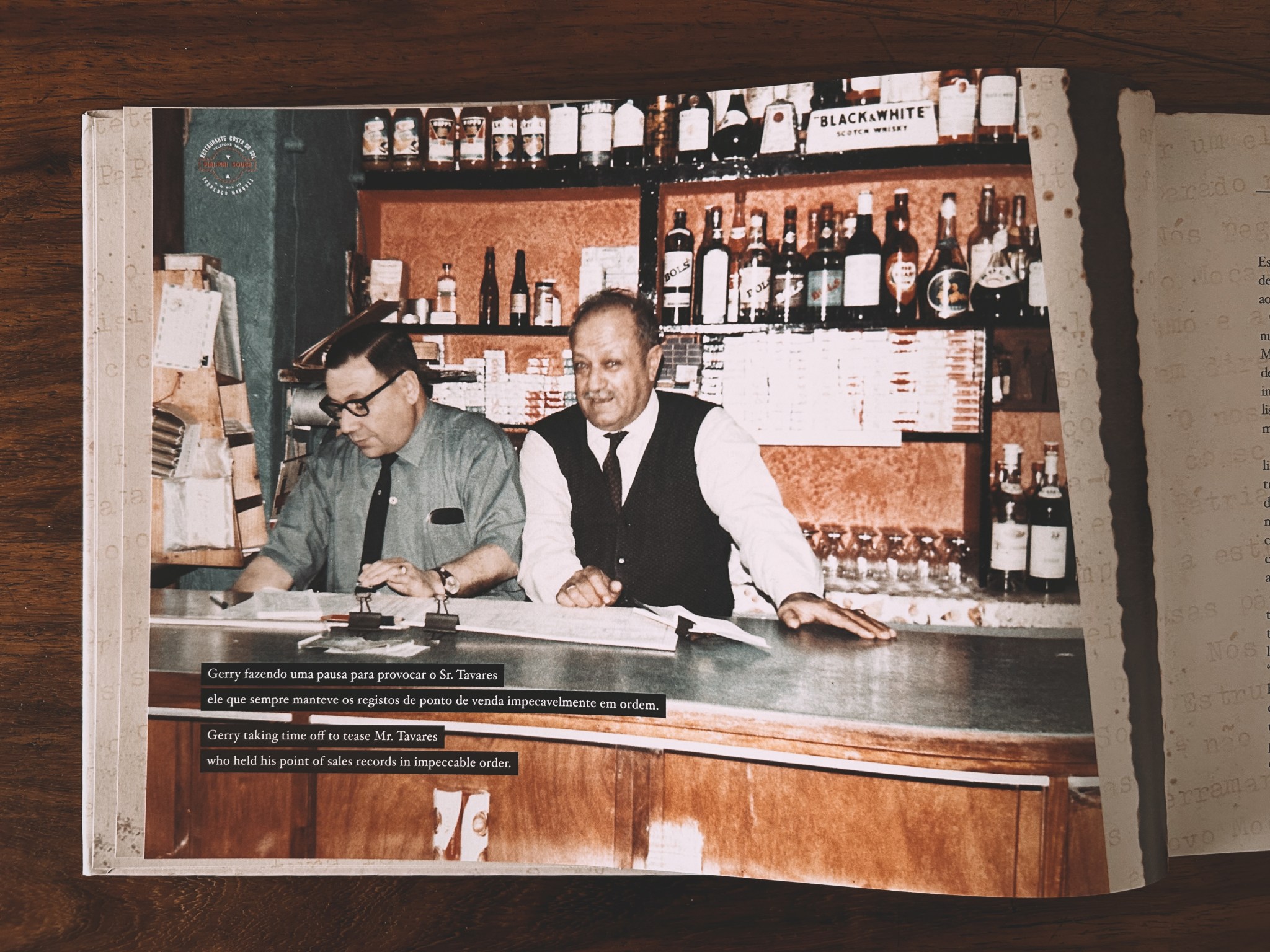

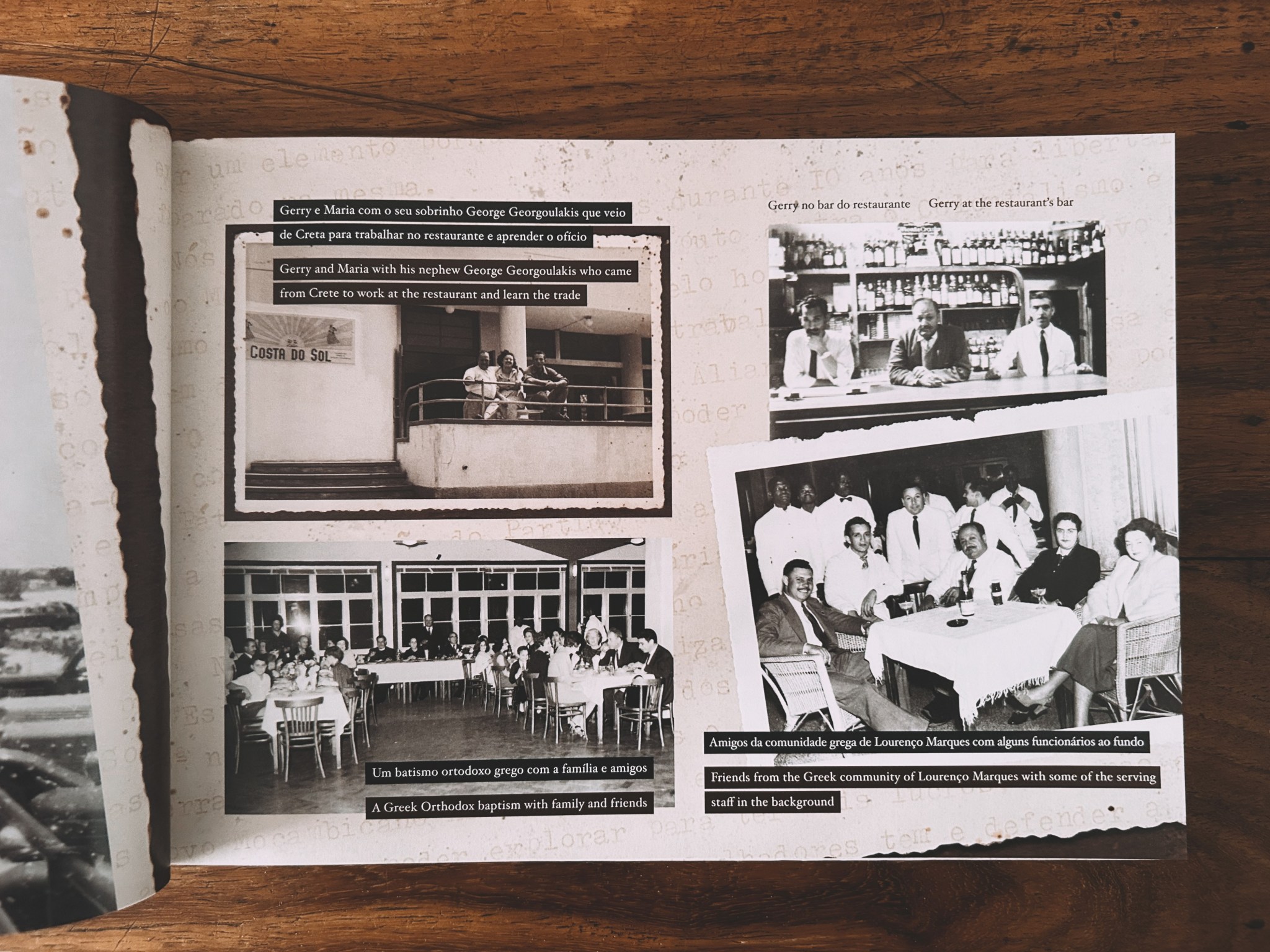

Without giving too much away, the drive of nascent Greek migrant families to sojourn far-flung lands and carve businesses out of meager resources is an admirable accomplishment. It is one that is seen in other countries with significant Greek populations such as Australia. The story goes that Gerri Petrakakis bought the “tea-room” from a Portuguese man when it had already been built in 1938. Gerry was invited to Mozambique by his brother John from Rethymno, on the Greek island of Crete.

In the years following, the restaurant operated with banging success both with locals and as an obligatory pit-stop for tourists coming to Lourenco Marques – home of the famous LM Prawns. The book goes into much detail recounting the various “colorful” patrons and their foibles.

Not long after Mozambique became independent of Portugal, Gerry Petrakakis died in 1978 of a cancer that had been ailing him for some years. The restaurant continued to operate under the stewardship of his wife Maria and son Immanuel, co-author of this book.

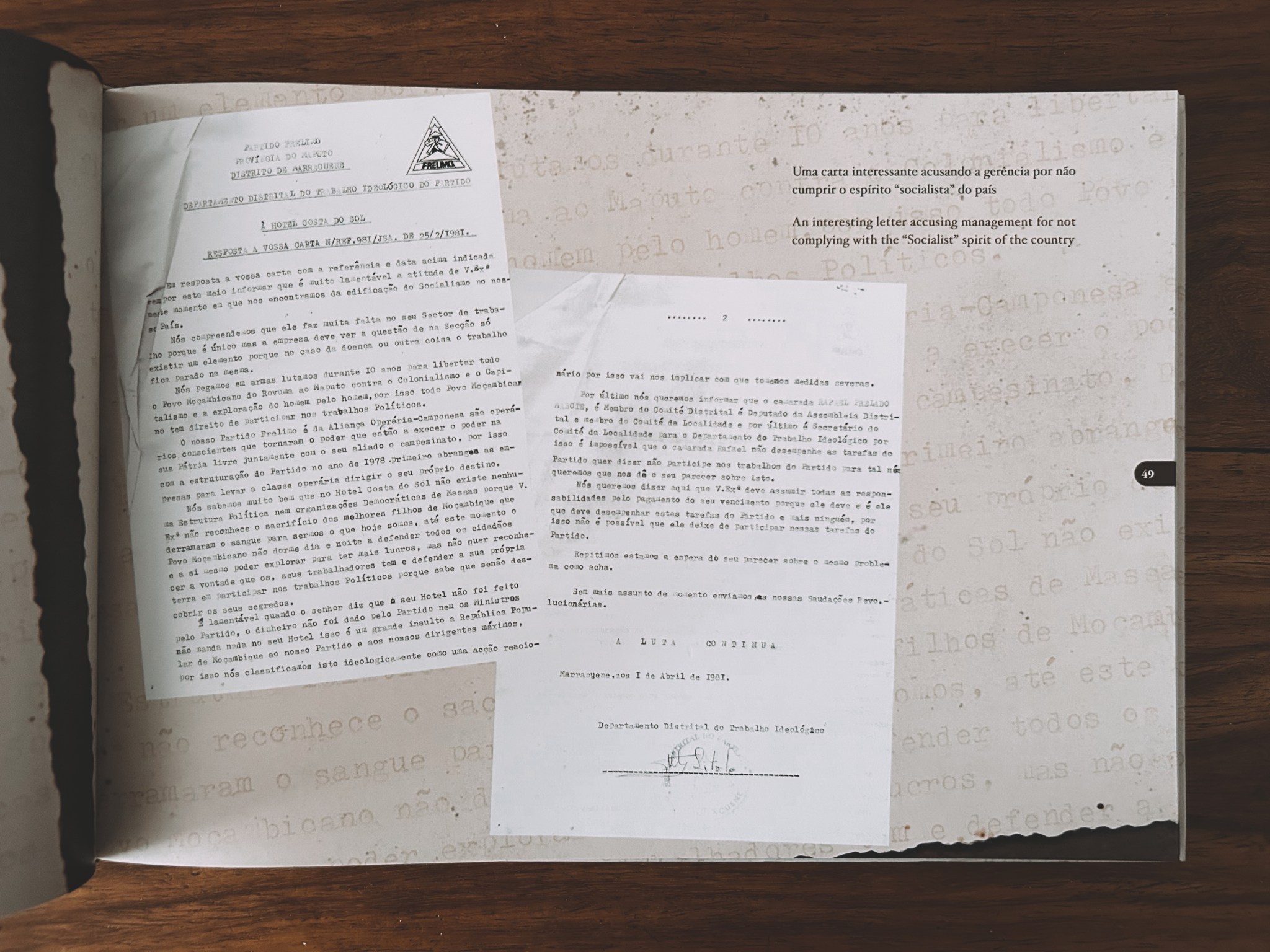

The Petrakakis family were of the few that had not left Mozambique and were forced to re-formulate their business as the country plunged into a socialist dystopia that everyone had long feared. The book is unapologetic (a sign of the times?) in that it quite openly reveals communications with the authorities. With reference to, shall we say, a difference of opinion, the State responds:

It is regrettable when you say your hotel wasn’t funded by the Party, the money wasn’t given by the Party, and the Ministers have no say in your hotel. This is a great insult to the People’s Republic of Mozambique, to our Party, and to our top leaders. For that reason, we classify this ideologically as a reactionary action that will imply our taking extreme measures.

This was the era in which the Party and the State were one. Democracy, was limited to coming together and agreeing to the same rhetoric. Anyone towing a different line would be considered a counter-revolutionary. In those years, the reach of the Party was so extensive that in every business or association there was a Secretary who would report back to the Party.

Decisions could not be made by the management alone, and if a choice had to be made between profitability and efficiency the Secretary would be able to veto so that ultimately the ideological outcome would prevail. It was more often than not that poorly informed Secretaries, lacking comprehension or business expertise and obscenely confident led a great many companies to bankruptcy.

The restaurant went on to have a very special place after the economic liberalization of Mozambique, counting Leonardo di Caprio as one of its visitors of international fame – who was in Mozambique during the filming of Blood Diamond.

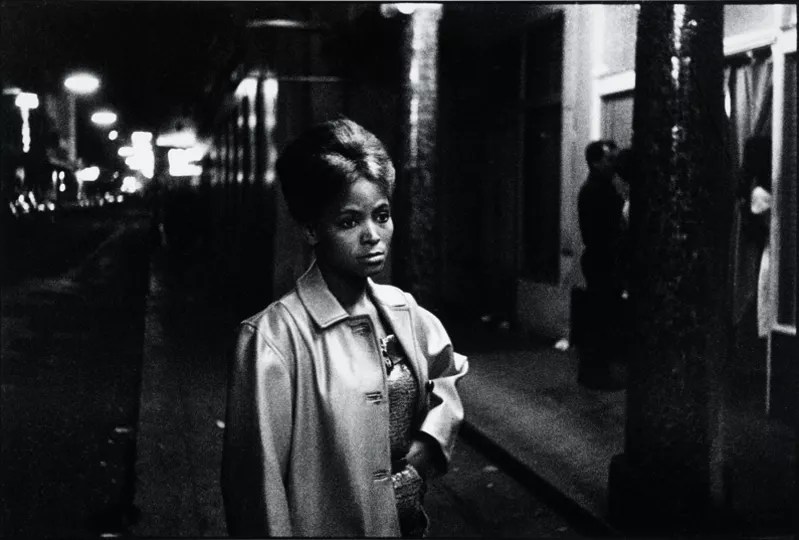

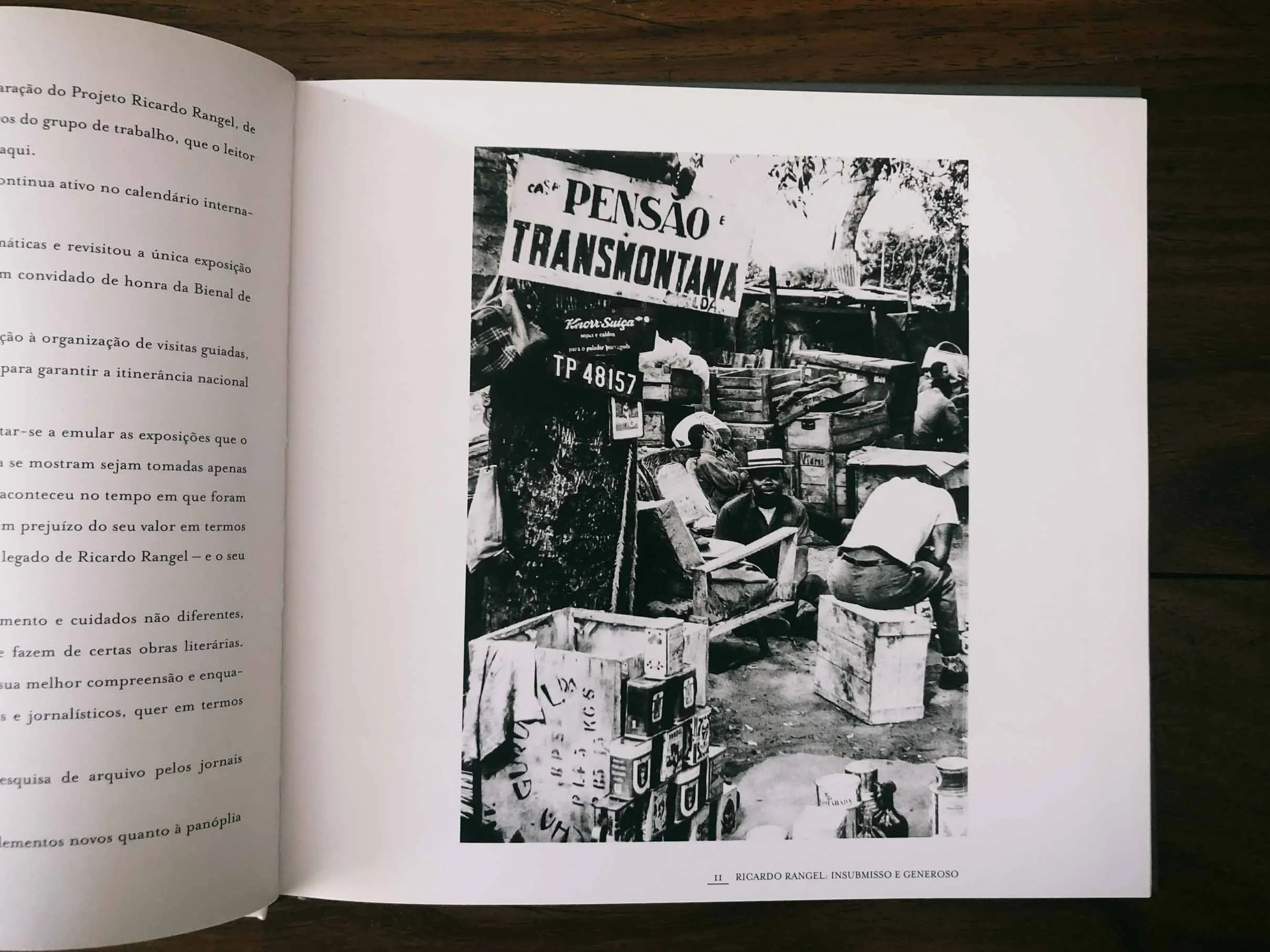

The histories told in the book by many of Rangel’s contemporaries suggest that he initially kept most of his material that would not pass the censor board private. His foray into journalism began at what is now Noticias for which he would provide photos. Owing to his ability, he was gradually given greater freedoms over his content which he gladly accepted and often used to throw jibes at the colonial administration.

The histories told in the book by many of Rangel’s contemporaries suggest that he initially kept most of his material that would not pass the censor board private. His foray into journalism began at what is now Noticias for which he would provide photos. Owing to his ability, he was gradually given greater freedoms over his content which he gladly accepted and often used to throw jibes at the colonial administration.